24,00 €

Potrebbero interessarti anche

Volti di Palmira ad Aquileia – Portraits of Palmyra in Aquileia

A cura di: Tiussi Cristiano

Facing English text

Formato: 21 x 30,5 cm

Legatura: Filorefe

Pagine: 144

Anno edizione: 2017

ISBN: 9788849234817

EAN: 9788849234817

UB. INT. : T523C V14b V42i

Contenuto

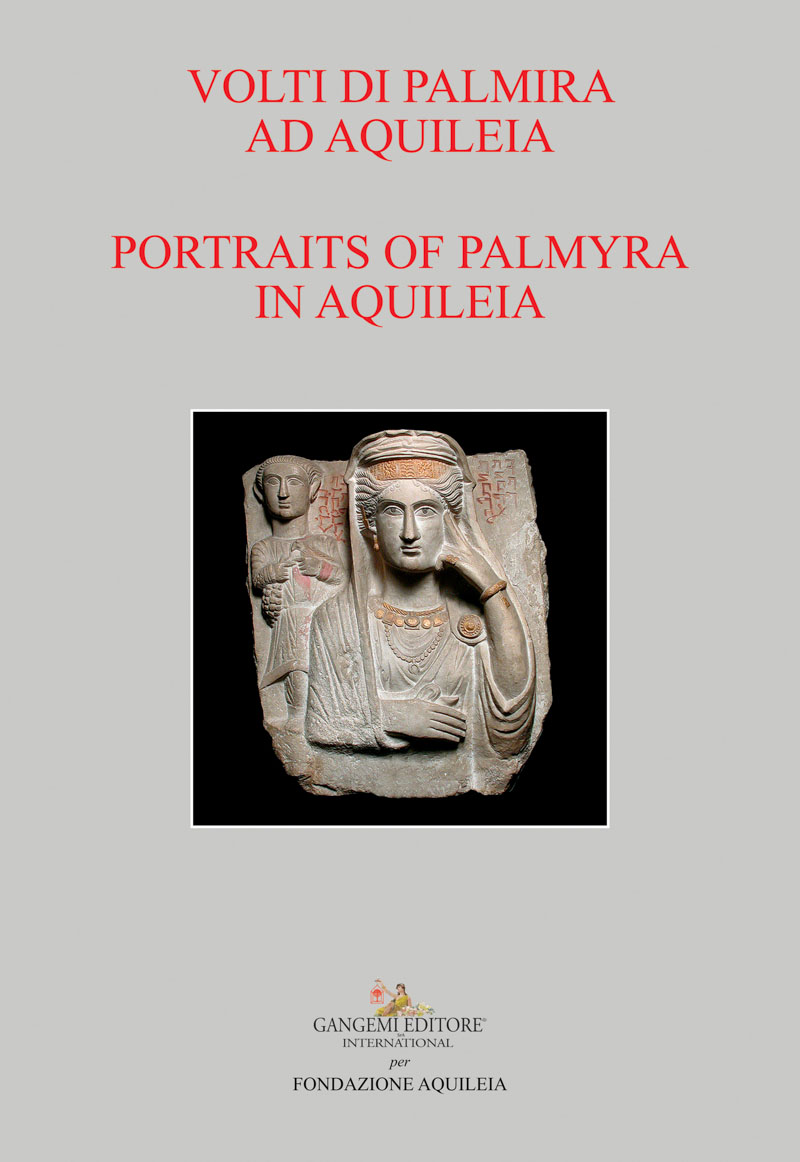

Un tempo città carovaniera e crocevia tra occidente e oriente, Palmira è uno dei siti archeologici greco-romani più sontuosi mai riportati alla luce, paragonabile a Pompei o a Efeso. La sua conquista nel maggio 2015 da parte delle forze dell’ISIS, e la distruzione di molti dei suoi più importanti monumenti, è stata una delle tragedie più dolorose e gravi che abbiano colpito il patrimonio culturale mondiale. così come la decapitazione, il 18 agosto 2015, del direttore Generale delle antichità di Palmira, l’archeologo Khaled al-Asaad, assassinato per “essersi interessato degli idoli”. alla sua eroica figura l’Italia ha dedicato corsi di laurea e sale nei suoi musei.

La storia dell’impero romano e la storia di Palmira sono profondamente intrecciate. annessa all’impero nel I secolo a.C., la cosiddetta “Venezia del deserto” costituiva uno snodo fondamentale per i commerci tra il Mediterraneo e la Mesopotamia. a conferma di relazioni frequenti e molto vitali, nell’antica Roma fioriva una solida comunità palmirena, come testimoniato dall’esistenza di alcuni bassorilievi, custoditi ai Musei capitolini, che riportano scritture in palmireno, uno dei quali viene esposto ad Aquileia.

Palmira era un centro di libertà, di anticonformismo, di multiculturalismo, un crogiolo di elementi diversi. Vi si intrecciavano le eredità dell’antica Mesopotamia, della Siria aramaica, della Fenicia, erano presenti elementi persiani, arabi, della civiltà greca e della cultura ellenistica, consistenti e vivi pur sotto la dominazione romana. eppure Palmira è sempre rimasta se stessa, né ellenizzata né romanizzata, ma forte della sua peculiare unicità.

Una grande e fiorente città pericolosamente vicina a popoli nomadi e barbari e a civiltà diverse fortemente espansive. Sono questi caratteri che l’avvicinano suggestivamente ad Aquileia, anch’essa centro di grande civiltà e cultura, sede di commerci, ma anche città di frontiera, spesso minacciata, ma vicina al diverso e proprio per questo con una vocazione al dialogo ed alla comprensione.

Il grande vicino di Palmira era la Persia, il grande vicino di Aquileia erano i popoli barbarici. aureliano era impegnato sul basso Danubio nelle guerre contro i barbari quando gli giunse voce della marcia che la regina palmirena Zenobia aveva intrapreso dall’Anatolia verso Roma. interruppe le ostilità, spostò accampamenti e legionari e portò le sue truppe verso il Bosforo, marciando verso Palmira, dove nel 272 fermò il tentativo di conquista. nel 274 aureliano celebrò a Roma la vittoria su Palmira facendo costruire un tempio dedicato al Sole di cui non sono purtroppo rimaste tracce.

Sia Palmira che Aquileia erano dunque luoghi di tolleranza e fruttuosa convivenza tra culture e religioni diverse, oltre che testimoni del fatto che diciotto secoli fa il Mediterraneo costituiva un’unità integrata non solo dal punto di vista dei commerci, ma anche di quello della circolazione delle idee e di canoni artistici e narrativi. ne troviamo traccia nei monumenti di Palmira, che mutuano il barocco tardo-ellenistico con influenze arabe e romane.

Once a caravan city lying at the crossroads between the east and the West, Palmyra is one of the most sumptuous Graeco-Roman archaeological sites ever brought back to light, comparably to Pompeii or Ephesus. its capture by ISIS forces in May 2015 and the resulting destruction of several of its most remarkable monuments were one of the most painful and serious tragedies for the world cultural heritage. and the same is true for the beheading, on 18th august 2015, of the General director of antiquities of Palmyra, archaeologist Khaled al-Asaad, who was murdered for “being interested in idols”. There are now master’s degree courses and museum rooms named after his heroic memory in Italy.

The history of the Roman empire and the history of Palmyra are closely entwined. annexed to the Roman empire in the 1st century BC, the so-called “Venice in the desert” represented a key junction for the trade between the Mediterranean Sea and Mesopotamia. Bearing evidence of the frequent and lively relations of Rome and Palmyra, a solid Palmyrene community thrived in Rome, as confirmed by some Roman reliefs bearing Palmyrene inscriptions, preserved in the Capitoline Museums: one of them is displayed in the exhibition dedicated to Palmyra in Aquileia.

Palmyra was a centre of freedom, non-conformance, multiculturalism, and a melting pot of different civilizations. The legacies of ancient Mesopotamia, Aramaic Syria, Phoenicia all blended there. Persian, Arab, Greek and Hellenic traditions stood firm and alive in spite of the Roman domination. and yet, Palmyra always remained an entity per se, neither Hellenized or Romanized, invariably strong in its peculiar unique identity. a great and thriving city, dangerously close to nomadic and barbaric peoples and to an alien civilization extremely prone to expansion. These features bring Palmyra suggestively close to Aquileia, another great centre of civilization and culture, a hub of trade, but also a border city, a neighbour to a different civilization, and therefore with a vocation for dialogue and cohabitation.

Palmyra’s great neighbour was Persia; Aquileia’s great neighbour were the Barbarian peoples. emperor Aurelian was fighting against the latter in the lower Danube area when he became acquainted that Palmyra’s queen Zenobia was marching across Anatolia towards Rome. he put an end to the war, moved military camps and legions and brought his army towards the Bosphorus, heading to Palmyra, where he eventually stopped Zenobia’s attempt in 272 ad. in 274 AD, Aurelian celebrated his triumph over Palmyra in Rome and had a temple built and dedicated to the Sun, of which unfortunately no traces remain.

Both Palmyra and Aquileia, then, were places of tolerance and fruitful cohabitation between different cultures and religions. They were also witness to the fact that eighteen centuries ago the Mediterranean Sea used to be an integrated unity, not only for trade but also for the circulation of ideas, as well as of literary and artistic styles. evidence of this can be found in Palmyrene monuments, where late Hellenistic Baroque elements are revisited with Arab and Roman influences alike.

Parole chiave

Condividi su